Forces of Friction: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction to Frictional Forces

Frictional forces are resistive forces that oppose relative motion between surfaces in contact. These forces arise from microscopic interactions between surface irregularities and are essential in everyday phenomena from walking to vehicle braking. Friction can be both beneficial (enabling traction) and detrimental (causing energy loss).

Key Concept: The force of friction always acts parallel to the contact surfaces and opposes the direction of intended or actual motion.

Let's examine three illustrative scenarios to understand friction fundamentals:

Experiment 1: Push an empty cardboard box across a smooth floor and release it. The box travels 1-2 meters before stopping. The decelerating force is kinetic friction, which opposes motion between contacting surfaces.

Experiment 2: Load the box with books and repeat the push. The loaded box travels a shorter distance. The increased normal force (equal to the total weight) proportionally increases the frictional force, demonstrating that friction magnitude depends on the perpendicular force between surfaces.

Experiment 3: Attempt to push a heavy bed that remains stationary. The applied force is insufficient to overcome the maximum static friction, which can exceed kinetic friction. This explains why initiating motion often requires more force than sustaining it.

Two primary friction classifications emerge from these observations: static friction (prevents motion initiation) and kinetic friction (opposes existing motion).

Kinetic Friction: Opposing Existing Motion

When surfaces slide against each other, kinetic friction acts opposite to the velocity direction. This force dissipates kinetic energy as heat and sound. The magnitude of kinetic friction follows:

The coefficient $\mu_k$ depends on both contacting materials and surface conditions. Notably, kinetic friction is generally independent of contact area and sliding velocity for most practical applications.

Example 1: Kinetic Friction Analysis

Problem Statement:

- Draw a free-body diagram for a stationary box of mass $m$ resting on a horizontal surface, labeling all forces.

- The box is now pushed horizontally with force $F_a$ exceeding the maximum static friction. The floor has kinetic friction coefficient $\mu_k$. Construct an updated free-body diagram during motion.

Solution (a):

For a stationary object on a level surface, two primary forces act:

- Weight: $W = mg$ acting downward through the center of mass

- Normal force: $N = mg$ acting upward from the surface

These forces are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction, resulting in zero net vertical force.

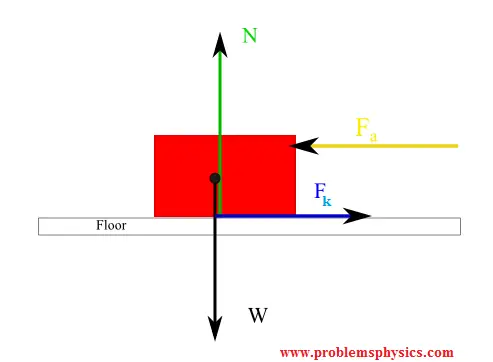

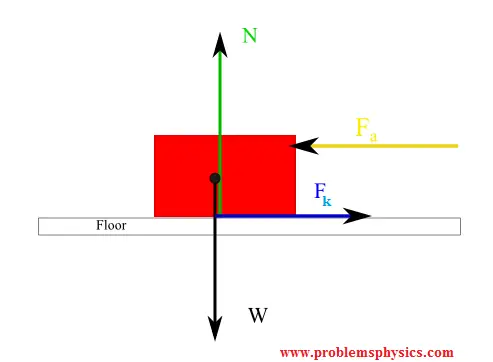

Solution (b):

Solution (b):

During horizontal motion with applied force $F_a$, four forces act:

- Weight: $W = mg$ (downward)

- Normal force: $N = mg$ (upward)

- Applied force: $F_a$ (horizontal, direction of motion)

- Kinetic friction: $F_k = \mu_k N$ (horizontal, opposite motion)

The net horizontal force $F_{net} = F_a - \mu_k mg$ determines acceleration via Newton's Second Law: $F_{net} = ma$.

Static Friction: Preventing Motion Initiation

Static friction acts between surfaces at rest relative to each other, adjusting its magnitude up to a maximum threshold to prevent motion. This adaptive quality enables objects to remain stationary despite applied forces. The maximum static friction is given by:

Crucially, the actual static friction matches the applied parallel force up to this maximum: $F_s \leq \mu_s N$. The static friction coefficient generally exceeds the kinetic coefficient ($\mu_s > \mu_k$), explaining why initiating motion requires more force than maintaining it.

Example 2: Static Friction Analysis

Problem Statement:

A horizontal force $F_a$ attempts to pull a box from left to right but is insufficient to cause motion. The surface has static friction coefficient $\mu_s$. Construct a complete free-body diagram and analyze the forces.

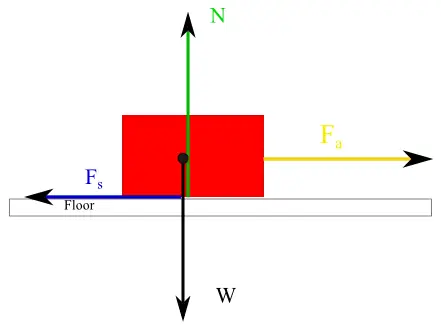

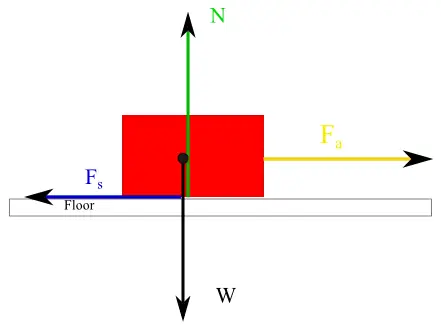

Solution:

When the applied force cannot overcome maximum static friction:

- Weight: $W = mg$ (downward)

- Normal force: $N = mg$ (upward)

- Applied force: $F_a$ (horizontal, attempted motion direction)

- Static friction: $F_s = F_a$ (horizontal, opposite to applied force)

Since there's no motion, static friction exactly balances the applied force: $F_s = F_a$. This equilibrium persists until $F_a$ exceeds $F_{s,max} = \mu_s mg$.

Key Relationships and Practical Applications

Friction Coefficients Comparison: Typically $\mu_s > \mu_k$ for the same material pair. For example, rubber on concrete: $\mu_s \approx 1.0$, $\mu_k \approx 0.8$.

Normal Force Dependence: Both friction types scale linearly with normal force, not contact area. This explains why heavy vehicles need stronger brakes and why friction doesn't increase with wider tires (though wider tires improve traction through other mechanisms).

Real-World Applications:

- Braking Systems: Kinetic friction converts kinetic energy to thermal energy

- Walking/Gripping: Static friction prevents foot/shoe slipping

- Engineering Design: Bearings minimize unwanted friction in machinery

- Earthquake Analysis: Static friction buildup and sudden kinetic friction release along fault lines

Summary of Friction Relationships:

$$

\begin{aligned}

\text{Static Friction: } & F_s \leq \mu_s N \\

\text{Kinetic Friction: } & F_k = \mu_k N \\

\text{Typical Relationship: } & \mu_s > \mu_k

\end{aligned}

$$

Understanding friction forces enables prediction of motion, design of mechanical systems, and analysis of everyday phenomena. These fundamental principles form the basis for more advanced topics in mechanics, including work-energy relationships and rotational dynamics.

Solution (b):

Solution (b):